Features

Interviews

Interview: Director Guy Maddin on the ghosts of cinema past and his new film The Forbidden Room

Filed under: Interviews

Guy Maddin's films have always had at least one foot planted firmly in a shadowy and beautiful cinematic past. Beginning with his first feature, the awe-inspiring Tales from the Gimli Hospital in 1988, Maddin's gaze seemed fixed backwards to a distant era in which the talking picture was still unfamiliar and strange. However, his sense of humour and narrative rhythms remained utterly contemporary. Like a punk rock F.W. Murnau, Maddin has garnered a feverish cult following with remarkable films such as My Winnipeg, The Saddest Music in the World, and Cowards Bend the Knee.

His new film, The Forbidden Room, is a hypnotic and twisted series of surreal tales, which intertwine and fold back on each other like some demon-possessed Russian nesting doll. It's a story within a story within a story times ten. Just when you think you know where the tale is headed, Maddin and his co-director Evan Johnson pull out the rug and you disappear into the next narrative. As visually alive as it is narratively nimble, the film begins on a submarine at the bottom of the ocean, filled with tasty flapjacks and unstable explosives. What Maddin and Johnson add to the filmmaker's classic visual accouterments, which include silent film inter-titles in a non-silent film, is a wonderfully warped and hallucinatory edge.

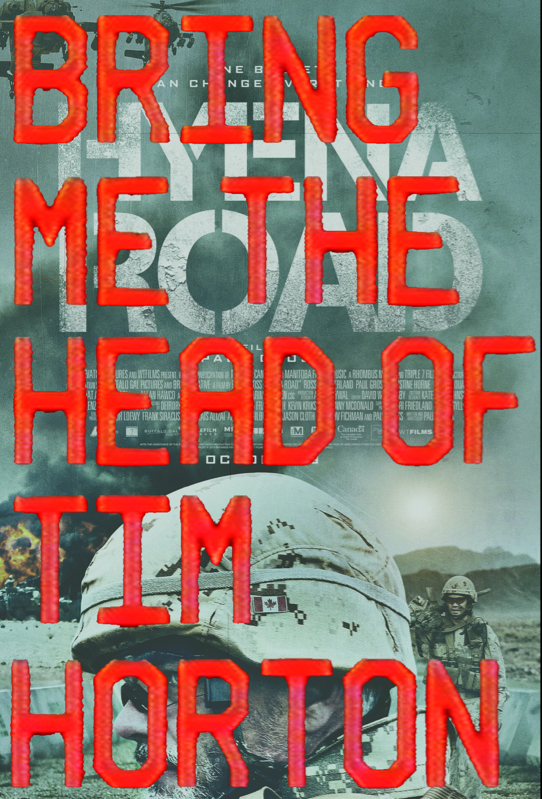

Maddin himself admits that same style has also been applied to Bring Me the Head of Tim Horton, his subversively irreverent look at the making of the Paul Gross war picture, Hyena Road. Half behind-the-scenes documentary and half cryptic skewering of modern war cinema, the film recently ran as an art installation at the Toronto International Film Festival and the New York Film Festival.

This shift towards contemporary styles and settings is indeed a conscious decision for Maddin, who admits that he may in fact be cured of his own haunted obsessions. Those obsessions which focused Maddin to look backwards, searching through the past, through old movies and old memories are now fading. In their place, we have Maddin's unforgettable films, the creative works of one of the most unique and fiercely individual voices in cinema.

Guy Maddin and Evan Johnson's The Forbidden Room premieres at Winnipeg Cinematheque on Friday, October 9 at 7pm.

"Keep the rust off my eyeballs"

Tony Hinds: Is it true The Forbidden Room began as an art installation, titled Seances?

Guy Maddin: It did, yeah. That was something I started secretly, as early as the 90's. I used to get short film commissions now and then, and when I was depressed because I didn't have a feature film project, I would accept short film commissions eagerly because it would usually mean I'd get $1000 and a director's fee and then, get a movie out there, and keep the rust off my eyeballs. I often didn't know what to shoot, so I got into the habit of shooting the synopses of lost or unrealized projects by my favourite directors. Way back in '94, I shot a film that was really using the plot of a lost Abel Gance movie, La Rowe. Turns out, it wasn't lost. I just thought it was. It's been released now. My version is 4 minutes long. Abel Gance's original is 4 hours long. So there's two versions of the movie: a 4 hour version and a 4 minute version.

TH: *Laughs*

GM: *Laughs* And then, I returned to Abel Gance for inspiration when I made the 2000 short film, Heart of the World. I was inspired by the plot of his film, La Fin Du Monde (The End of the World) and once again, it turned out not to be lost.

TH: *Laughs* Oh no, not again.

GM: *Laughs* Once again, I made yet another Abel Gance movie that I thought was lost, but wasn't, so there's two versions of that, as well. But undeterred, I decided... there's such a huge mother load of lost films, Academy Award-nominated films, films made by really important filmmakers, all the canonical greats, that great generation that straddled the silent and talking picture era. Even right on up to the exploitation era, the Grindhouse Golden Age, and even Cambodian filmmakers who were murdered by the Khmer Rouge, and all the stuff suppressed by The House of Un-American Activities Committee, films by blacklisted people, marginalized people, by Native Americans, by women in sexist cultures -- which is every culture -- but especially violently sexist cultures who had their films destroyed and careers curtailed.

I was haunted by the absence of these films, but inspired by the mother load of synopses and engaging recontextualisations of history just sitting there, waiting to be redeployed. And so, I thought of this project where I could make my own short film adaptations of these long lost features the way I had with the two Abel Gance pictures. And so, I came up with the idea of adapting them into short films and loading them onto a website, which the National Film Board of Canada is now hosting. It will be launched early in 2016. While I was researching these projects, I took on my former student, my best student, Evan Johnson (Maddin's co-director on The Forbidden Room) who had become a friend, to help me with research. But he was outstripping me by thinking up new conceptual wire frames for the project, and pretty soon I thought I better name him co-creator before he's my boss and I was his researcher.

"The French John Wayne Gacy"

TH: Can you talk a little bit about the project's funding?

GM: There's a great deal of enthusiasm about interactive and new media at the state support level in Canada, but the budgets available to artists in those areas are not as big as they are in film. We also realized the project would take a long time, there would be a long time between features for me, so we decided to make a feature film that would be a companion piece, a sibling piece to accompany the internet project, so that we could help finance the Seances project with the feature film, and that the two could enrich each other and keep each other company like siblings, equally loved by the parents and by me. So The Forbidden Room came out first just because, unlike parents with siblings, we had to work on them one at a time. And now, we're going back to work to finish up Seances.

TH: It's really amazing to learn that each of the chapters, for lack of a better term, were assembled one at a time. Is that correct?

GM: That's right, yeah. It was Frankensteined together. The first half of the shoot was three weeks in France, in Paris, in public at the Centre Pompidou. Anyone strolling in there could just watch us shoot. We were in the foyer, before you have to pay to go into the museum proper. All sorts of people came, there were sometimes hundreds of people watching, sometimes ten, sometimes one. There was always the one scary guy, I don't know who that was... sort of the French John Wayne Gacy...

TH: *Laughs*

GM: ...sitting there with faint clown make-up outlines on his face, watching me the entire time. It was fun. And the same thing at the Phi Center at Montreal, who actually ended up producing the movie and saving it from its graveyard spiral. It was doomed to some sort of fiscal extinction, but the people at Phi saved it and hosted the second half of the shoot. Every now and then, visitors could watch from above, and literally food and gum wrappers and cigarette butts are falling down onto the set, and we just kept all that stuff in.

TH: That actually goes hand in hand with that idea you've talked about (in the past), the notion of embracing the mistakes. I mean, shooting in public has gotta be...

GM: It's encouraging more mistakes. And maybe even the act of shooting in public was a mistake for all I know. *Laughs* It encouraged a lot of happy accidents that I had grown to fear would never happen again in the digital world. But Evan Johnson will tell you, he figured out ways in the colour timing and cooking of the images to encourage accidents in the digital realm where they normally don't happen. I'm very happy again, and full of mojo and ready to go. We're kind of leaving this old timey movie stuff behind us now, and probably Bring Me the Head of Tim Horton is more of a transitional step towards some uncertain future, but I feel more energized than ever.

Hyena Road

TH: Bring Me the Head of Tim Horton sounds so amazing. [Note: I had not seen it at the time of the interview. Having now seen the film, I can attest that it is amazing and very funny.] Am I right to assume that there's a certain sense of humour in your approach, someone of your talent covering the making of a Paul Gross movie?

GM: Well, the whole idea seemed preposterous. It seemed preposterous to Paul Gross too. His producer Niv Fichman has been a producer of mine as well, and a friend. He produced The Saddest Music in the World and a few of my shorts: Sissy Boy Slap Party and a few others. Sometimes against my will, he's insisted I make them. And I've always been glad I've made them. He and I have a great relationship because half the time we're trying to strangle each other and I throw these queeny hissy fits all the time. He slaps some sense back into me, and we embrace and go bathe each other in some spa somewhere. I don't know... everything's cool, everything's cool.

TH: *Laughs*

GM: But during one of our more desperate modes in Camp Forbidden Room, Evan and his brother Galen Johnson (The Forbidden Room's production designer, music designer, and graphic artist) and I were complaining about how much money Paul Gross gets for his films, and lamenting how poor we were, as we were into the fourth year of making (The Forbidden Room.) *Laughs* And we hadn't been paid in ages, so someone, I don't even remember who, suggested we do a making-of (documentary) just for some quick bucks. So I quickly phoned Niv. And Paul, whom I'd met just a few months earlier and gotten along with really well... he's a relentless quipper. The two of us got into these sort of quip-offs, where we'd delight each other, and delight in ourselves probably as much as in each other, until tears were streaming and snot was flying from our self-loving faces.

So as perversely stupid and ill-advised as the whole project was, we were both keen to dive into it. Now I'm not so sure how smart it is to do such as thing, but there is some precedent where really cool making of projects have come from really great movies. One thinks of the making of Fitzcaraldo (Burden of Dreams) and the making of Apocalypse Now (Hearts of Darkness,) and there's this film called Cuadecuc, vampir about the making of Jess Franco's Count Dracula, which is really an amazing movie. That's my favourite. And there's countless others. But Evan Johnson is really the putative director. Evan, Galen, and myself all took co-directing credits. Evan cut all this footage together, Galen did the music design and the graphic design, which is a lot, and what I did was kind of played myself. In this team of mischievous making-of insurgents, I'm kind of the graying figurehead, slumped sleeping in a safe house somewhere, while the Brothers Johnson go out a reap the real havoc.

"I'm cured of my movies"

TH: Going back to something you said earlier about leaving the old timey movie stuff behind... do you mean old timey in the sense that -- I mean, it's probably true that you haven't really made a film that doesn't take place in a period setting, or the distant past.

GM: Yeah, maybe My Winnipeg, which is partially in the past, and my complaining seems to come from the present. It's really just a backward looking movie.

TH: But is that something you're actively looking to move away from?

GM: I think so. I mean, you know... I've been doing it longer now than those decades existed, living in the '20s and '30s since Tales from the Gimli Hospital, which was finished in 1988. That's 27 years and those two decades were only around for a couple years. *Laughs* You know, the first couple years of the '30s. It's enough. I've repurposed them to my satisfaction now. I think I got it this time.

TH: When you think back to Gimli Hospital, which is a film I'm still madly and deeply in love with... it's such an amazing film!

GM: Oh, thank you.

TH: But when you look back on that trajectory from Gimli Hospital to The Forbidden Room, do you think there was a change in your approach, or in the things that interested you?

GM: Yeah, I came to understand what was driving me in my dream life and my so-called creative life to do what I was doing. I had a lot of unfinished business with the past... with some loved ones who had left suddenly. I don't know... it was just this way... this backwards way in which I allowed myself to grow up. And even delayed growing up. swiss replica watches

TH: Sure.

GM: Then, I began to understand some of the fairy tales my blind grandmother had told me at the foot of my bed. I began to realize I was understanding all of cinema in those terms and I just had to work it through. And for decades now, I've been entering all films and all books through the fairy tale door and getting my bearings inside and saying how much or how little each work of art I was encountering was in fact a fairy tale and finally, having to abandon that point on the compass entirely and look at them differently. I'm a slow learner, but I've doggedly stuck it out.

Even the act of making a film is very therapeutic, and with each subject you tackle, you kind of spend so much time with it, you're tired of it by the time you're done. You cure yourself of one obsession at a time. I'm cured of many things by now. Don't worry, I'm still messed up enough to keep making movies. I'm cured of my movies. But I hope other people aren't. There are still times when I feel as imperfect and sometimes disappointing as my movies have been to me, and how they've failed to accomplish exactly what they wanted. I think in some ways they've partially succeeded. Many artists want a species of immortality for at least a little while, for a few years past their death date. I hope people in the future will get something of the feelings I was trying to impart to them from my projections, so we'll see.

TH: I think they will, and already are.

GM: Yeah, I'm getting surprised by some people's reactions. Journalists are now treating the films much differently. These movies have been around long enough that some of them came to these movies as teenagers, and had time to think about them. Maybe not think about them, but feel them. The films haven't changed, but maybe the context they're watched in has.

Don't miss Guy Maddin and Evan Johnson's The Forbidden Room, which premieres at Winnipeg Cinematheque on Friday, October 9 at 7pm.

Note: This interview has been edited/condensed for length.

Tags: Guy Maddin, The Forbidden Room, Evan Johnson, Galen Johnson, Bring Me the Head of Tim Horton, Hyena Road, Paul Gross

Tony Hinds is a Canadian writer who studied film at the University of Winnipeg. In addition to ShowbizMonkeys.com, Tony has reviewed films for Step On Magazine and The Uniter. You can find Tony on Twitter.

SBM on Social Media